Exploring a new index to better manage urban water systems

Understanding how to enhance urban water systems

Students in the Master of Engineering Leadership in Integrated Water Management program worked on a capstone project with industry partner GHD, the only accredited provider of the Water Sensitive Cities Index (WSC-I) in North America.

In 2023, three students in the Master of Engineering Leadership in Integrated Water Management program – Charu Bhanot, Kimia Nazokkar and Malwika Chitale – worked on a capstone project with industry partner GHD, the only accredited provider of the Water Sensitive Cities Index (WSC-I) in North America.

The WSC-I is a tool originally developed in Australia for water management professionals and decision makers to manage water services more holistically in the face of increasing pressure from rapid population growth, aging water infrastructure and extreme precipitation events and drought.

The students had three primary objectives for their capstone project: review what indicators are currently being used by municipalities across the country, conduct a survey to determine if the WSC-I resonates with Canadian stakeholders, and develop a roadmap for implementation that includes funding models.

What’s a water sensitive city?

A water sensitive city is one that is liveable, resilient, sustainable and productive.

As the students describe in their report, the Water Sensitive Cities Index was developed as a “unique benchmarking tool that combines aspects of water and green infrastructure management to determine standardized scores for cities based on a predetermined set of goals.”

Decision makers can use the index to better understand how shifts in governance, community capital, equity, productivity, ecology, urban design and adaptive infrastructure can guide capital investment to help cities be more resilient to water supply issues.

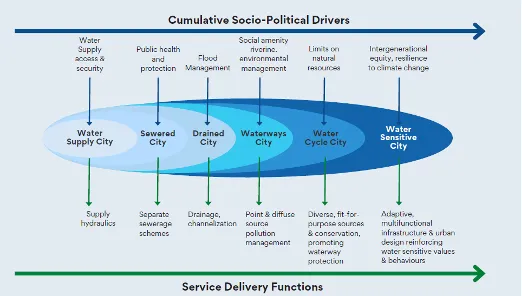

As shown in the diagram below, using the index can help cities move from a focus on water supply to cities that are truly water sensitive, where infrastructure and urban planning reinforce water-sensitive values and behaviours.

SWOC analysis of the current landscape

The three students analyzed eight water indices currently in use by completing a strengths, weaknesses, challenges and opportunities (SWOC) analysis. They identified opportunities for WSC-I as a benchmarking, planning and communication tool that could result in enhanced urban water management and better collaboration among stakeholders.

Surveying water management experts

To assess water professionals’ interest in a new index, students surveyed 25 individuals from municipal governments, water service boards, private-sector companies and urban planning.

“We wanted to see if the language and concept of water sensitive cities resonated within a Canadian context,” says Charu.

“We asked them for their input on the water sensitive cities framework and whether they thought it could be used in their current models, as well as for their ideas about who should be the ‘owner’ of the index,” says Malwika.

Proposing a governance model

The students then developed a proposed governance model consisting of three key partners: government (funding), the private sector (expertise) and academic institutions and non-profit organizations (data). They developed a fund charter, estimated the costs associated with implementing the index and explored various funding options.

“We also developed an implementation canvas showing everything required to roll out this index nationwide, from key stakeholders to who would fund it,” says Charu. “We thought this was an innovative way of telling a big story in an easily understandable format for a wide range of audiences.”

Importance of a Water Sensitivity Measurement Index

“The key differentiator of this index is that it puts water front and centre,” says Malwika. “Many other indexes or measures of sustainability focus on emissions, whereas the Water Sensitive Cities Index helps urban planners and water management professionals make better decisions about water.”

That’s going to be increasingly important. “There’s going to be significantly more pressure on water infrastructure in the coming years,” says Kimia.

“This tool can help Canadian cities more holistically manage their water resource in the face of population increases and extreme climate events.”

Kimia is a strong advocate of integrating AI into water infrastructure management. “Sensors can detect small problems before they become major issues, letting you better manage and maintain your water network,” she says. “In the not too distant future, every city is going to be a smart city that uses data to drive decisions.”

Integrating learning into water infrastructure capture

This project was completed as part of the Water Infrastructure Capstone course taught by Dr. Cheryl Nelms, General Manager of Project Delivery at Metro Vancouver.

Kimia, Malwika and Charu say that Dr. Nelms spent considerable time at the start of the course getting to know each student and their specific professional interests, and then offered students a choice of capstone projects that would enable them to work directly with an industry partner while stretching their skills and applying the knowledge they’d gained in the business and technical courses over the prior two semesters.

The students had very positive feedback from both Dr. Nelms and GHD, and they may have the opportunity to present the results of their capstone project to the Canadian Water Network in 2024.